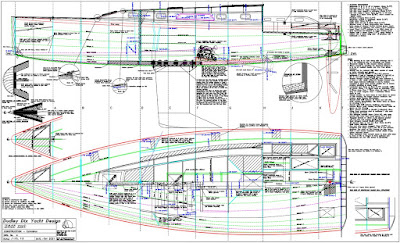

David Edmiston, amateur builder of the Didi 120 “Passion XI”, is getting as much of the work done as he can while the hull is upside-down. Each time that I have turned the hull of one of my own big boat build projects it has rained the next day, turning my hull into a paddling pool. That possibility encourages a builder who doesn’t have a workshop large enough to house the new build to do much work that might otherwise have been left for when the boat was upright. I once visited a builder of a Didi 34, with the hull still inverted. He had the interior almost fully complete, including all painting, trims varnished and locker and cabin doors varnished and hung. All of that work had been done by a meticulous builder to a standard that few can achieve.

David is also doing some of the work needed for mechanical systems in his boat. Photo numbering continues from my previous post about this project.Photo 36. The

hole through the hull has been enlarged to suit the fibreglass stern tube and

the P-bracket has been wedged at the height and angle need to align with the

shaft. The dowel is fitted through the cutless bearings of the stern tube and

P-bracket exactly as the final shaft will be. The P-bracket has wooden wedges

securing it at the correct height and angle for least binding of the dowel in

the bearing. If the stainless steel shaft is available then it can be used

instead of the dowel but the light weight of the dowel makes it much easier to

work with. The dowel must be truly straight and round or accuracy will be

sacrificed.

Photo 37. The

stern tube and P-bracket have now been bonded into the hull with filled epoxy.

The stainless steel shaft is now being used to ensure absolute accuracy of the

installation.

Photo 38. This

shows the installation of the P-bracket on the inside of the hull. A plywood

gusset has been glassed into the hull, making a solid mounting that is braced

by the bulkhead. The P-bracket has been trimmed to remove unneeded length and

bolted to the gusset. The hole through the hull is cut slightly over-size so

that the P-bracket can align itself precisely with the shaft, with the epoxy

filler taking up the slight slack.

Photo 39. The

engine end of the shaft has been accurately set up on a board that is bolted to

the engine bearers to coincide with the intended output shaft alignment, both

in height and angle from horizontal. In this design, the stern tube is long

enough to pass through and be bonded into a hull frame for long-term rigidity.

This area of the hull has been made very rigid by extending the engine beds aft

as girders to minimise hull flex in a part of the hull that might otherwise bend

under heavy backstay tension.

Photo 40. The rudder shaft has been fabricated by an engineering company. It is stainless steel round bar of maximum thickness where it passes through the bearings in the hull bottom and is tapered both ends. The top end is also machined with a keyway to receive hardware for tiller and a radial drive wheel that will be used for connecting the autopilot. The latter can also be used to connect wheel steering for owners who prefer a wheel to a tiller. The flat bar tangs transfer the loads between the shaft and blade, which will be built over the shaft assembly.

Photo 41. The

hole for the fibreglass rudder port has been cut through the bottom of the hull

and the port dry-fitted in place for setting up accurate shaft alignment. The

rudder will turn in acetal bushings that are fitted into the port and the

fitting through the cockpit sole. Without that upper bearing to ensure accuracy

of alignment of the rudder port, so this is done with temporary framing and

clamps, seen at the bottom of the photo.

Photo 42. The

rudder shaft has been suspended at the correct level to allow checking of all

machining.

Photo 43.

The rudder port is braced on the inside with plywood gussets fore/aft on

centreline and transverse. The fore/aft gussets land on the backbone and the

transverse gussets land on plywood doublers that reinforce the bottom plywood. The

gussets are glassed over, with the glass extending onto all adjacent

structures, making a strong and rigid structure to contain the loads applied by

the rudder.

Photo 44. With the rudder port, stern tube, P-bracket and keel shoe installed, it is back to the outside to complete the hull. The glass reinforcement of the centreline has been laminated, tying the two bottom panels together. The glass is also worked over the keel shoe and onto the stern tube and P-bracket to further bond these to the wooden structure.

Photo 45. The wood surfaces have been prepared for finishing by filling any imperfections, fairing and sealing with epoxy. The light layer of fibreglass in the epoxy coatings is not structurally required but toughens the surface against light damage.

Photo 46. The aft end of the hull has received careful treatment. A sharp corner on a wood surface doesn’t hold finishes well and is easily damaged, with the potential for water to enter through unseen damage. This corner has been rounded to a radius that will hold the finishes and allows the bottom glass to be wrapped onto the transom. The corner is then built back to a sharp edge with reinforced epoxy to create a much tougher corner. There is good reason for this. Water flowing off the bottom at low speed hangs onto the surface and is dragged around the corner, with that water bubbling along behind the boat when it need not be there. A sharp corner encourages the water to break away to make a cleaner wake, with less drag.

Photo 47. After

completion of the epoxy coatings and final fairing, primer coats have been

applied, followed by topside paint and the bootstripe.

Photo 48.

Fitting out and painting the interior has continued whenever weather conditions

prevent work being done on the outside. Here is owner and amateur builder David

Edmiston wielding his paint brush on aft cabin cave lockers.

The next post in this series will cover hull turning and the start of deck construction.

For information about our designs, please visit our Dudley Dix Yacht Design for our main website or our mobile site.